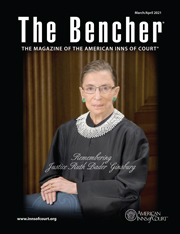

Heroes Never Die: A Dissent from RBG’s Death

The Bencher—March/April 2021

By Rupa G. Singh, Esquire

Ideals are like the stars: We never reach them, but, like the mariners of the sea, we chart our course by them.

—Carl Schurz, German American political leader in the 1800s

As an appellate lawyer and a woman standing on the shoulders of pioneers who paved my way, I greatly admire Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—or RBG, as she was dubbed. However, I had not studied her writings beyond scholarly summaries in seminars or journals. The two times I heard her speak live were from afar, allowing for no interaction. Nor did I have much occasion to apply, in my business-focused appellate practice, the equal rights jurisprudence for which she was best known. So, while I was aware of her groundbreaking work and well-deserved celebrity, RBG did not touch my day-to-day life in any palpable way.

Or so I thought. Her passing affected me so immensely, shaking me to the core, that I felt as if a protective, guiding hand had been lifted from not only my head, but from our country’s back, leaving us both adrift. Then I heard Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky say during a seminar about the Supreme Court of the United States’ October 2020 term that we are grieving that much more for RBG because she was a hero in a time when there aren’t many heroes in our profession. It dawned on me then that not only was RBG a true real-life hero, but such a relatable one that she made us believe we could be heroes ourselves.

Her superpower was her brain, reflected in her pen. In eighth grade, she wrote an editorial for her school newspaper about the five greatest documents the world had known to date. With clear-eyed brevity, she made the case for why the United Nations Charter should join the Ten Commandments, the Magna Carta, the British Bill of Rights, and the U.S. Declaration of Independence as documents that benefitted humanity “as a result of their fine ideals and principles.”

Her ability to write and speak persuasively continued to be on full display in her teachings, speeches, and writings as a law professor at Rutgers University and Columbia Law School. She was one of the most winning appellate advocates at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU); a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit; an associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States; and a sought-after public speaker and officiant throughout her career.

Surprising for someone whose words and work proved so revolutionary, she advocated incremental change, inviting everyone along instead of dragging them to a desired conclusion about equality under the law in all respects—parental estate administration, dependent benefits for military spouses, social security benefits, access to public education, pay discrimination, voting rights, and reproductive justice, among others.

Even in her powerful dissents, she tried persuading instead of berating the majority, using accessible, everyday English to discuss why the other justices’ interpretation of complex legislation or jurisprudence was mistaken.

In her influential dissent in

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, she candidly noted that her male colleagues did “not comprehend or [were] indifferent to the insidious way in which women can be victims of pay discrimination” and put the “ball” in Congress’ court “to correct this Court’s parsimonious reading of Title VII.”

And she was successful, with Congress’ enactment in 2009 of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. Six years later, in

Shelby County v. Holder, she explained that invalidating an anti-discrimination mechanism in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that applied to historically segregated Southern states when “it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” How RBG’s dissenting words will inspire legislators and advocates to reinstate voter protections remains to be seen.

RBG appears to have stopped using the traditional phrase I “respectfully” dissent precisely because she respected those with whom she disagreed. It seemed hypocritical to her to pretend that she admired the majority’s reasoning while explaining why it was fundamentally mistaken or incorrect. Based on unspoken mutual respect, she bravely and candidly disagreed with her colleagues’ analysis while trying not to criticize their motives or intelligence. In an era of growing incivility in political, legal, and civic discourse, RBG modeled how to consistently take the moral high ground without being disingenuous or artificial.

Equally heroic was her authenticity, that combination of vulnerability, humility, and feminine sensibility, that made all of us identify with her as the hero next door, if not the hero within us. RBG’s brilliance and many firsts could have made her inaccessible, if not for her candid acknowledgment of her weaknesses combined with her petite stature and seeming physical frailty. She freely discussed her limitations in the kitchen and as a high school cellist.

Despite a love of opera and art that could make her seem elitist, RBG allowed her humanity to come through when she shared anecdotes about receiving advice from her in-laws on balancing marriage, motherhood, and career. Graceful to the core, RBG frequently switched the conversation from herself to spotlight and thank her personal heroes, including her mother, her in-laws, and her husband, as well as her professional role models, including Professor Vladimir Nabokov at Cornell University and ACLU advocates Pauli Murray and Dorothy Kenyon.

RBG remained true to her feminist voice in her personal and professional life, living the equality she championed as an advocate and judge. Even her devotion to her husband was based on a partnership built on the inseparable combination of mutual respect and romantic love. Without ever criticizing marriage as a patriarchal institution, she exemplified the incremental changes that could modernize and strengthen it. Instead of taking offense that women’s wardrobe choices garner public attention in a way that men’s don’t, RBG also incorporated her iconic fashion sense into “dissent” collars to amplify her feminist message. She assumed the mantle of her unsolicited celebrity in a way that helped more than one generation, particularly of women and girls, reimagine a life in the law as fulfilling and cool all at once.

RBG will live on if we, and hopefully future generations, continue to chart our course by her example. That need not mean enduring personal tragedy in early childhood with mature dignity; overcoming overt employment discrimination despite being the law school valedictorian; writing the definitive textbook on sex discrimination; co-founding a path-breaking ACLU project; marrying our staunchest admirer for all the right reasons; surviving and nursing others through multiple bouts of cancer; ascending to the male-dominated U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court of the United States; and making it hip to be a petite, bespectacled legal nerd.

Rather, honoring RBG’s legacy could just mean pretending to be slightly deaf to unkind words or criticism, as her mother-in-law advised and as RBG confessed to doing personally and professionally; choosing persuasion over accusation in our speech and writing, as RBG did skillfully from at least the eighth grade; and striving for moderation even in our impassioned efforts to create lasting change in our chosen sphere, as RBG modeled in her thoughtful appellate advocacy and careful judicial dissents.

For me, how I might carry on RBG’s legacy was brought home yet again by someone else’s words; this time, those of our nine-year-old daughter. The youngest member of our family is usually more concerned with perfecting her gymnastics front flips and pulling off a soccer hat trick than reflecting on feminist trailblazers or equality under the law. Nevertheless, she was visibly moved by a KPBS film tribute to RBG that our family watched. After being quiet through dinner that night, she said thoughtfully, “I wish we could dissent from someone’s death. If so, I dissent from RBG’s death.”

It made me smile, cry, and marvel at her elegant ability to simplify how I could transform into meaningful action my unavailing grief for someone I mistakenly thought never touched my life tangibly. Because I now aspire to persuade, advocate, and make difficult decisions by asking what my hero, RBG, would do in that situation, I proudly join in my daughter’s dissent.

Rupa G. Singh, Esquire, is a certified appellate specialist who handles complex civil appeals and critical motions in state and federal court at Niddrie Addams Fuller Singh LLP, an appellate boutique. She is founding president of the San Diego Appellate American Inn of Court, married to her equal, and the proud mother of three RBG groupies.