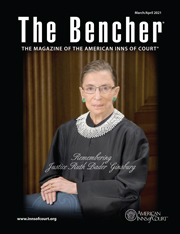

Justice Ginsburg: A Voice of Reasons

The Bencher—March/April 2021

By Keith Bradley, Esquire

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the late associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, was known for her vigorous dissents. There is even a biography of her by that name, “I Dissent.” But surely every justice prefers to write majority opinions.

Her being so often in dissent was a reality of the Supreme Court of the United States and its composition during the years she sat on it. When Ginsburg joined the court, its chief justice was William Rehnquist, a conservative appointed by President Richard Nixon, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was known as the “swing vote” on 5–4 cases. When I clerked for Ginsburg a decade ago, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts had replaced Rehnquist, and Justice Samuel Alito had replaced O’Connor, a shift that was widely expected to make the court more conservative.

Any assessment of Ginsburg’s service on the court should bear in mind her persistent experience of dissenting. A justice uttering a dissenting opinion is, at the same time, witnessing a majority decision that the justice believes to be wrong, possibly deeply wrong, and likely on an issue of substantial importance. Ginsburg watched that happen again and again, over decades.

Yet, she never lost her composure, and she never gave up on the possibility of persuading her listeners, including her colleagues, through respectful, rational argument. The tone of her dissents is noticeably cool, especially by comparison to some of the more heated rhetoric that has appeared more recently. As I write this, the Supreme Court has just issued a stay in

Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, N.Y. v. Cuomo. A concurring opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch suggests the dissenters are “shelter[ing] in place while the Constitution is under attack,” while the chief justice, unusually, finds it necessary to defend his dissenting colleagues as fulfilling their constitutional duties while simply disagreeing with the majority’s analysis.

Compare this exchange to Ginsburg’s dissent in

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. The court held that Ledbetter’s 180-day deadline for filing an employment discrimination claim began when Goodyear established her pay at a rate lower than comparable male colleagues and that she did not gain a fresh claim with each lower-rate paycheck.

Ginsburg famously announced her dissent from the bench, a rare occurrence that she reserved for the most important disagreements. The issue at stake, involving gender equity and the redress for violations of it, was surely at the core of Ginsburg’s convictions. And the vigor of her dissent inspired the incoming 111th Congress to abrogate

Ledbetter as one of its first actions. Yet the dissent itself contains none of the strident tone that is visible in the Diocese of Brooklyn opinions and so many others from recent years.

Here is her most direct criticism of the majority: “The court’s approbation of these consequences is totally at odds with the robust protection against workplace discrimination Congress intended Title VII to secure. …This is not the first time the court has ordered a cramped interpretation of Title VII, incompatible with the statute’s broad remedial purpose. …Once again, the ball is in Congress’ court. As in 1991, the Legislature may act to correct this court’s parsimonious reading of Title VII.”

She certainly complained that the court got it wrong, but she did not question its motives or its sincerity. She attacked the decision, not the deciders, and the bulk of her opinion was an explanation of her reasons and argument.

In a 2004 symposium on Ginsburg’s life and work, Linda Greenhouse titled her contribution “Learning to Listen to Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” She wrote about how then-attorney Ginsburg’s words in the 1970s ended up changing the mind of Justice Harry Blackmun. As we reflect on Ginsburg’s life and work 16 years later, I think about her side of that story. Ginsburg persistently spoke to people who disagreed with her, and she showed again and again that if you choose your words carefully, you can get people to hear them. That is how she described her strategy in the great equal rights cases of the 1970s. She designed cases to show how gender discrimination can be harmful to men as well as women—in order, she said, to present the problem in a way that would make sense to the nine men on the Supreme Court.

Ginsburg saw firsthand the fruits of that effort, not only in the decisions in those cases, but in the long-term evolution of those men’s views. She was very conscious that Rehnquist regularly dissented in her 1970s equal rights cases. Yet, he later joined the judgment when, in 1996, she wrote for a majority that the Virginia Military Institute could not exclude women.

More recent examples are also visible, particularly in a case that might be considered Ginsburg’s swan song on equal rights.

Sessions v. Morales-Santana involved a citizenship law applicable when a person has one U.S. citizen parent and one non-citizen parent. If the parents were married, the child could acquire U.S. citizenship if the U.S. citizen parent had lived in the United States for five years before the child’s birth.

The rule was the same if the parents were unmarried and the U.S. citizen parent was the father. But if it was the mother, the statute required only that the mother lived in the United States for one year before the birth.

Morales-Santana invalidated that exception. Notably, the court had considered the same issue already, in

United States v. Flores-Villar. In that earlier case, the court divided evenly, but five of those same justices then formed the majority in

Morales-Santana. Clearly something changed, and it is easy to imagine that the force of Ginsburg’s reasoning, presented to her colleagues with respect rather than rhetoric, was an important factor.

The campaign that Ginsburg fought as an advocate in the 1970s—for equal treatment without regard to sex or gender—was among the most important of our time. Many of the issues on which she dissented over the years were of comparable significance. One could have forgiven her if she had lost her patience sometimes, or even lashed out in anger. Yet, no matter what mistakes she saw, and no matter the consequences, she never lost sight of the fact that errors can be corrected, and people can be persuaded, if you are able to talk to them.

Keith Bradley, Esquire, is a partner in the Denver, Colorado, office of Squire Patton Boggs. He is a Barrister member of the Judge William E. Doyle American Inn of Court and served as a law clerk for Ruth Bader Ginsburg from 2010–2011.